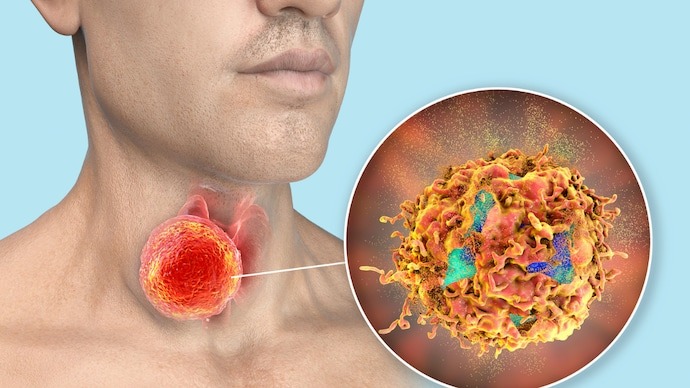

Over the past two decades, medical experts have observed a rapid increase in throat cancer—particularly oropharyngeal cancer, which affects the tonsils and the back of the throat. The primary cause of this surge is the human papillomavirus (HPV), a group of viruses already known for causing cervical cancer. In fact, oropharyngeal cancer has now become more common than cervical cancer in the United States and the United Kingdom.

A leading risk factor for spreading HPV to the mouth and throat is through intimate contact involving the mouth. While this might be surprising, it’s important to understand how HPV transmits, how it can lead to oropharyngeal cancer, and what can be done to reduce risks. Below, we break down the key points, including the role of vaccination, safe practices, and awareness.

1. Understanding the Increase in Oropharyngeal Cancer

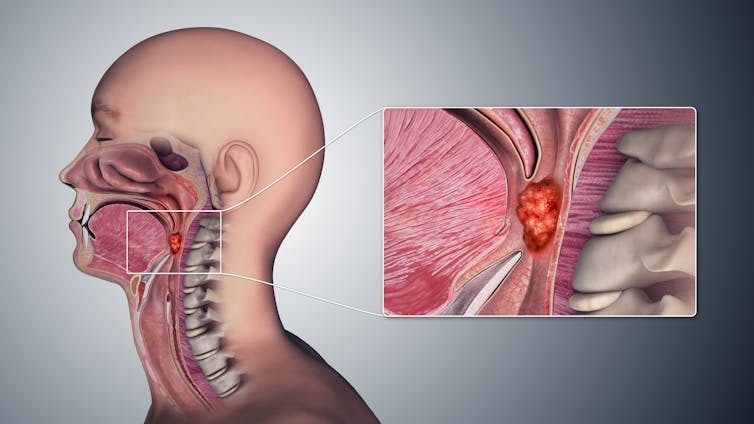

Oropharyngeal cancer affects the middle section of the throat, including the tonsils and the base of the tongue. Though once comparatively rare, the incidence of these cancers has risen sharply in western countries. Experts attribute most of this rise to HPV infections.

Why Has It Become So Common?

- Cultural and Behavioral Shifts: Over time, attitudes and behaviors around intimacy have evolved, contributing to a higher likelihood of mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-body contact.

- HPV Awareness Gaps: While HPV’s connection to cervical cancer is widely known, its link to throat cancers has only recently started receiving the spotlight.

- Lack of Routine Screening: Pap smears and related tests have helped lower cervical cancer rates. No widely practiced equivalent screening exists for the throat, making early detection harder.

Without interventions like vaccination and education, specialists predict that oropharyngeal cancer may continue to rise.

2. How HPV Spreads to the Throat

HPV is transmitted via skin-to-skin contact, commonly through close personal contact. In the context of oropharyngeal cancer, multiple studies show that having several lifetime partners—especially involving mouth-to-body contact—increases the likelihood of acquiring HPV infections. This risk goes up substantially once a person has had contact with six or more partners in this way.

Why Does HPV Lead to Cancer in Some Individuals?

- Persistent Infection: Most people’s immune systems clear HPV infections naturally within a couple of years. However, in a small group, the virus remains.

- DNA Integration: When the virus lingers, it may integrate into the host cells’ DNA, potentially triggering cancerous changes over time.

- Vulnerable Tissues: The throat area, particularly the tonsils, can be susceptible to prolonged HPV infection, increasing cancer risk.

It’s vital to note that not everyone who is exposed to HPV through intimate contact develops cancer. Genetic factors and overall immune health play major roles.

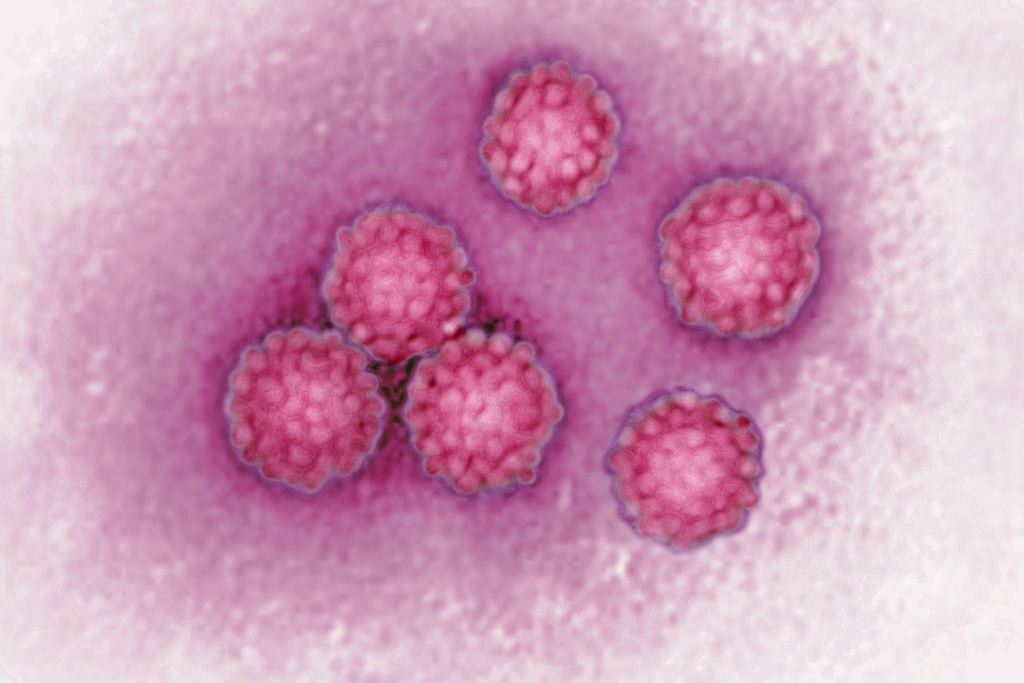

3. HPV Basics: From Cervical Cancer to Throat Cancer

HPV encompasses more than 100 strains, some of which pose minimal risk while others are strongly associated with cancer development. High-risk strains can cause cell mutations in various parts of the body, including the cervix, anus, and throat. In many instances, the immune system can eliminate the virus before it causes harm. However, if the virus persists, it can lead to cellular abnormalities that eventually become cancerous.

4. Role of Vaccination in Prevention

One of the most effective strategies to combat HPV-related cancers is vaccination. Initially, the HPV vaccine was introduced primarily to reduce cervical cancer in females. However, newer evidence supports its effectiveness in lowering HPV infections in other body areas as well.

- Vaccination for Girls

- High Coverage for Herd Protection: When more than 85% of girls in a community receive the HPV vaccine, overall viral transmission drops significantly. This also indirectly protects others.

- Reduced Spread: If fewer individuals carry high-risk HPV strains, the overall likelihood of exposure diminishes.

- Vaccination for Boys

- Gender-Neutral Policy: Recognizing that HPV-related cancers can affect any gender, many countries (including the UK, Australia, and the US) now recommend vaccinating both girls and boys.

- Addressing Coverage Gaps: Relying solely on vaccination among girls leaves potential gaps. Vaccinating boys ensures broader community protection and directly reduces their risk of oropharyngeal cancer.

5. Challenges to Widespread Vaccine Adoption

Although vaccination is a critical tool, achieving high rates of coverage isn’t always straightforward:

- Vaccine Hesitancy

- Concerns About Safety: Despite extensive studies demonstrating the vaccine’s safety, misinformation can spark fear.

- Misconceptions: Some believe vaccinating adolescents for HPV might encourage earlier or riskier behavior, although research does not support this claim.

- Pandemic Disruptions

- Missed Vaccinations: School closures and healthcare disruptions during global health crises interrupted scheduled vaccine programs.

- General Skepticism: Heightened skepticism about vaccines in some communities can reduce overall uptake.

- Geographic Variations

- Inconsistent Access: Vaccination rates vary by region, with some areas achieving strong coverage and others lagging significantly.

- Travel and Transmission: High coverage in one area doesn’t fully protect individuals who connect with people from regions with lower vaccination rates.

6. Practical Prevention Measures Beyond Vaccination

While getting vaccinated is one of the best defenses against HPV, additional steps can help lower your risk:

- Regular Medical Check-Ups: Early detection of signs—like ongoing throat discomfort or unusual lumps—can improve treatment outcomes.

- Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Good nutrition, regular exercise, and avoiding tobacco products support a stronger immune system.

- Safe Practices: Limiting the number of intimate partners, using barriers (where feasible), and maintaining open communication with partners about health history can reduce the odds of contracting HPV.

- Stay Informed: Knowledge is power. Understanding how HPV spreads and the benefits of vaccination can lead to better decisions about personal and family health.

7. Looking Forward: Hope for Declining Rates

Medical experts are optimistic that oropharyngeal cancer rates can be curbed if vaccination coverage expands and public awareness improves. In communities with comprehensive vaccine uptake among all genders, there’s potential for a significant decrease in HPV-related cancers over the coming decades.

Nevertheless, continued efforts are needed to address vaccine hesitancy, broaden access, and promote health education. Organizations, schools, and healthcare providers can work together to dispel myths and emphasize the vaccine’s importance. Moreover, adults who did not receive the vaccine during adolescence may still be eligible, depending on national health guidelines.

Conclusion

The rising incidence of HPV-related throat cancer underscores the importance of awareness, prevention, and proactive healthcare. While intimate contact involving the mouth is a known transmission pathway for HPV, protective measures—especially vaccination—offer hope for reducing this risk. Encouraging vaccination for all eligible individuals, maintaining safe personal habits, and seeking timely medical advice are central to safeguarding health.

By acting now, we can help ensure a healthier future. If you have questions about HPV or vaccination guidelines, speak with a qualified healthcare professional. Knowledge, precaution, and community-wide efforts are key in reversing the upward trend of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer.